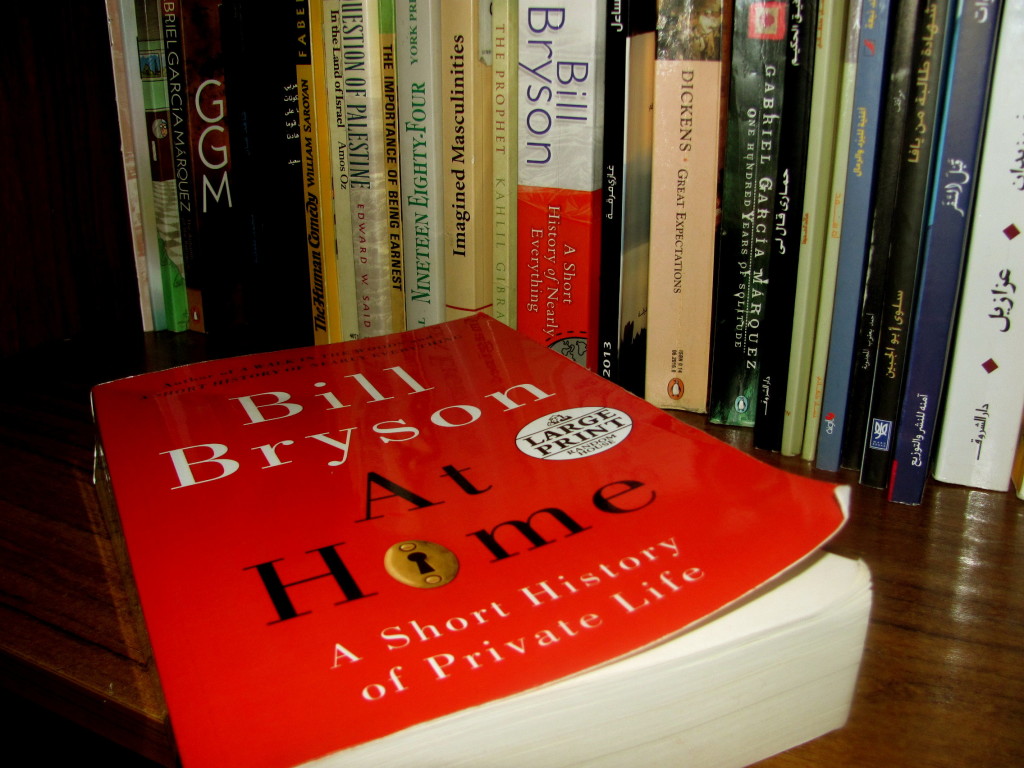

"If your a product designer, architect or industrial designer you must read this book! The 1850’s was a boom in design & invention. People invented things that had no purpose. It must have been a remarkable time. This book tells of countless stories of that remarkable time of invention. Bill Bryson goes room to room in his English home telling stories; problems and success’ of design, invention, and patent infringement." -Book review by Bart Brejcha

- 1 Chapters

- 1.1 The Year

- 1.2 The Setting

- 1.3 The Hall

- 1.4 The Kitchen

- 1.5 The Scullery and Larder

- 1.6 The Fuse Box

- 1.7 The Drawing Room

- 1.8 The Dining Room

- 1.9 The Cellar

- 1.10 The Passage

- 1.11 The Study

- 1.12 The Garden

- 1.13 The Plum Room

- 1.14 The Stairs

- 1.15 The Bedroom

- 1.16 The Bathroom

- 1.17 The Dressing Room

- 1.18 The Nursery

- 1.19 The Attic

- 2 Reception

- 3 References

As a product designer it is important to understand the history of the items we design. From the first telephone call to knowing the person who developed the recipe for Hydraulic Cement, whom by the way never collected royalties and died poor. Telling a story about a product’s history can lead to better relationships with customers too, as designers set themselves apart not just as design educators but product designers with a story. From a product designers perspective, the book “At Home, A Short History of Private Life” is charmingly warm and witty as the author moves from room to room of the past & modern home. Often restlessly from the kitchen to the bathroom through the Attic, to look at how and why basically the history of products as they exist in each place.

The First Chapter starts with Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace at the 1851 Great Exhibition. In order to create the greatest glass building ever assembled there were many problems to overcome. From inventions for glass production to mechanically how to erect such a structure. Homes in the 1700’s were taxed on the size of the windows not by an appraiser as it is done today. That tax went away at the same time glass production made new strides.

Bill Bryson discusses those problems with style and storytelling finesse like no other. The way he elaborates is just simply engaging. For example, Bryson explains that when the American addition to the 1850 world exhibit arrived by ship, the American organizers did not include enough money to transport the shipment from the shipping docks to Hyde Park, where the exhibit was housed. Bryson so elegantly explains the air of discontent for the United States in those times, ‘Congress in a mode of parsimony refused to extend funds, so the money had to be raised privately.’ To fuel even more discontent for the United States from a world perspective, the American organizers didn’t pay to set up, nor man the exhibit for the required five months. “Americans were little more than amiable back woodsmen not yet ready for unsupervised outings on the world stage.” notes Bryson. Peabody, an American in England stepped in to pay the final dollar amount needed to sustain the shipment. “So when the displays were erected it came as something of a surprise to discover that the American section was an outpost of wizardry and wonder. Nearly all the American machines did things that the world earnestly wished machines to do – Stamp out nails, cut stone, mold candles – but with a neatness dispatch, and tireless reliability that left other nations blinking.” From Samuel Colt’s repeat revolver to a harvesting reaper that did the work of 40 men were almost no one believed the reaper could do all it was said it could do till it was brought out to a local farm and proven.

Several chapters later Bryson helps us become fascinated by every day items. For example, in the chapter about the kitchen, he tells a compelling story about the invention of the can for preserving foods. Then many years later able to discuss the modern day can opener we know today was was patented in 1925. It is strange that the can opener was invented so many years later.

In ‘The Cellar’ chapter, Bryson tells us of building materials that were used, from stone to cement, all while discussing costs with dates of first use, and associated trends. In this chapter we learn how one inventor developed a compound that changed the fate of the United States. Hydraulic Cement, probably the single most important invention for building the Erie Canal, connecting the farmlands of the Midwest to New York City and ensuring NYC’s economic supremacy. Bryson tells us if not for this canal, Canada would be ideally set up to become the powerhouse of North America. Canvass White the engineer who developed the special water-resistant mortar patented his recipe that made America what it is today. White died after years of court battles, but never received royalties and spent all his money in court only to lose time and time again. The problem solving and product innovation that had to occur in the short 8 year span to make the Erie canal possible also showed the world that American innovation was a force to be reckoned with. From a product designers point of view patents and patent infringement ideals set the tone for our careers. “Probably no manufactured product in history – certainly none of greater obscurity – has done more to change a city’s fortune that Canvass White hydraulic cement.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canvass_White

In the chapter “The Passage” we learn more about Thomas Edison in a time when the United States was “Smitten with the idea of progress that they invented things without having any idea whether or not those things would be of any use.” Did you know Thomas Edison was into making Concrete houses out of a molds? “Concrete was one of the most exciting things of the nineteenth century.” Edison formed the Portland Cement Company and after building a huge plant in New Jersey started on plans to pour homes of concrete. By 1907 Edison was the fifth – biggest cement producer in the world. “Edison’s dream was to make a mold of a complete house into such concrete that could be poured in a continuous flow, forming not just walls and floors but every interior structure – baths, toilets, sinks, cabinets, door jambs, even picture frames.”

If you’re an industrial designer, product engineer or architect, read this book. I read it from the the designer perspective and I couldn’t put it down. – Bart Brejcha

http://www.amazon.com/At-Home-Short-History-Private/dp/0767919394