How do you make nuclear energy safely and cheaply? The answer is simple: Build it with well-tested existing technology and put it in a safe location, in a place where it can be easily cooled, and safe from events such as earthquakes or tsunamis.

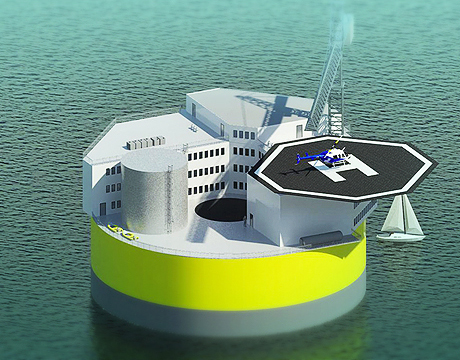

Jacopo Buongiorno, associate professor of nuclear science and engineering at MIT, and his colleagues have been floating just such an idea. Their bobbing reactor design is the offshore oil rig of the nuclear world, and they hope it will address the needs and fears of a power-hungry world.

Try convincing an investor or government to build a new reactor and you’re bound to come up against some resistance. Safety concerns are just part of the equation. “Uranium is cheap,” says Buongiorno. “The problem is that the reactor is an expensive, complex structure. You don’t get any revenue during construction, which may take five to ten years—not an appealing investment.”

Buongiorno’s simplified design could be built in pre-existing shipyards at a much speedier pace than on-site construction. Newport News for instance, managed to assemble the aircraft carrier Gerald Ford in three years, fitted with two nuclear reactors. “They could build a nuclear power plant, and it could be towed to anywhere there’s a coast line, moored a few miles offshore,” he says.

Scalable and Safe

The spar-type platform Buongiorno has in mind is small compared to what shipyards are capable of building these days. It can be scaled to fit various needs and can accommodate as much as a 1,000-MW plant. If a floating reactor of that size could be built in a year or two, nuclear power could become competitive with natural gas and coal.

Convincing inventors is the first step; convincing everyone else, the second. Buongiorno believes the inherent safety of his design will do just that. A state-of-the-art light water reactor at sea, connected to shore only by its AC cable, addresses two lessons learned in the nuclear era: Avoid the possible loss of a heat sink, and don’t let radiation contaminate land.

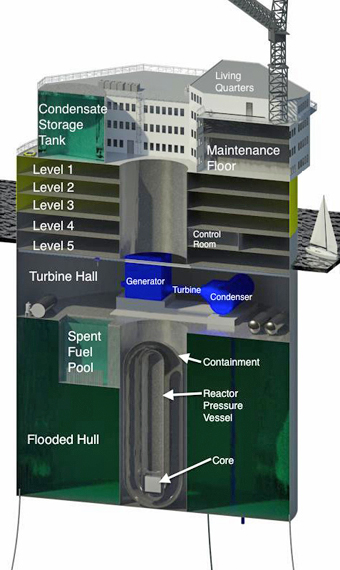

Offshore, of course, the heat sink is limitless. The reactor part of the rig is tucked in to a cylinder that stays underwater. In a situation with a loss of power, the ocean is still there for cooling. In a worst-case scenario, any radioactivity would dissipate quickly. “The ocean is a huge body of water and dilution works,” says Buongiorno.

Submerged, it’s kept safe from falling planes and other unforeseen events, while earthquakes and tsunamis will do little to disturb the reactor in waters at least 100 meters deep. It would simply bob up and down with the tsunami waves.

Heat Removal

The plan also eliminates worry about the reactor destroying habitat by warming waters. The reactor would draw water from the bottom, and after cooling, would be discharged at the same ambient temperatures as water at the surface. According to Buongiorno, marine life would be no more disturbed by the rig than they would be by a cruise ship.

For spent fuel, the gap can also be flooded with fresh water from the condensate storage tank during refueling operations. Refueling would be performed every four to five years, and spent fuel assemblies transferred to the onboard spent fuel pool, which has storage capacity up to the plant’s lifetime, with a passive decay heat removal system that uses the ocean as its ultimate heat sink.

It’s humans who would most likely to be disturbed by the idea of a floating reactor. But Buongiorno is quick to point out that the elements of his plant are not that novel. “One of the selling points is that it is a combination of established technologies,” he says, “We don’t need a new reactor, we don’t need any new material, we don’t need anything that is high risk for development.”

What Buongiorno does need is regulatory approval, and the interest of a reactor vendor and a shipbuilding company, all of which he believes may come together soon. “We don’t anticipate any show stoppers,” he says.

[divider]

Article written by Michael Abrams, July 2014 for ASME.org